THE BARBARISM OF REASON

Apex

PART ZERO: Introducing Goya (1746-1828)

Section 0: Introduction

Perhaps no artist more fully expressed the conflict and confusion of the Post-Enlightenment age as Goya. Once triumphant, Goya’s later work would be his claim to fame, reflecting the tormented soul of a man desperately searching for goodness in the world and finding little of it anywhere. For the late Goya, there was no Light and Dark, no clear Good and Evil. Simple, triumphant narratives were displaced by an awareness of the grotesque and barbaric aspects of human nature. Reason could not conquer it; in fact, it could only fuel it further.

To properly understand the Late Goya, which I will define as the Goya after his mental and physical illness in 1792-3, we must begin much earlier. The Early Goya is an entirely different artist and man, but this period is critical for his later disillusionment at the horrors of ideology and human barbarity. From counting some of the finest nobility of the continent among his patrons and friends, to living a reclusive lifestyle and turning his lens towards the common people (the pueblo) of Spain, Goya was shaped by the political and social turmoil of his age as well as his own psychological struggles. One can only fully grasp the Late Goya’s pessimism by understanding the Early Goya’s triumphalism.

PART ONE

Section 1: The Early Goya

Prior to 1789, Goya was most well-known for being a talented court portraitist and religious painter. His work was innovative, although it was clearly inspired by the titan of Spanish Baroque painting, Velazquez. Goya’s inclusion of himself in a number of portraits and paintings of this period, as well as his “embrace of spatial and compositional ambiguity, and most of all his psychological incisiveness” are all echoes of Velazquez, as Stephen Eisenman has put it quite clearly. In 1786, Goya was promoted to the post of Pintor del Rey (Painter to the King). In 1788 he painted The Family of the Duque de Osuna.

The portrait is an excellent example of Goya’s exceptional skills as a portrait artist. He picks up on minute details in each individual member’s facial expression and body language. The first note in that vein is the relaxed expressions of the various members of the family. All six appear wholly comfortable, even as a portrait was a lengthy ordeal. What makes that doubly interesting is that family portraits like this were rare at the time in Spain. The Duke, although in uniform, is not standing at attention, nor is he presenting any grim air of seriousness; instead, he looks like a loving father enjoying an afternoon with his family.

As a whole, the family is organized in a pyramid formation, with the Duke at the peak. Interestingly, the Duke and Duchess may have been raising their own children, rather than hiring someone else to do so, a peculiarity for the time period. The Duchess is even depicted with a book in her hand, perhaps an indication of her intellect. She was actually a member of the Royal Economic Society of Madrid, of which her husband was president. The parents and children appear to be closely connected and affectionate with each other. When we also note that the two sons are at play in the bottom left with their own toys, it is possible that the Duke and Duchess had embraced new French and Swiss pedagogical ideas around the special importance of childhood and the important role of parents in their children’s education.

Goya’s skills were in demand across the country and elsewhere, and by the late 1780s he was receiving more commissions than he could fulfill. In April 1789, Goya was promoted to Pintor de Càmera (Court Painter) to Charles IV. In 1790, Goya was elected to the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Carlos (Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Carlos), one of the most progressive art academies in Europe. Goya’s rise seemed unstoppable. Two self-portraits reflect Goya’s triumphant self-appraisal.

The simpler of the two self-portraits, Self-Portrait in a Cocked Hat, depicts a Goya of staunch resolve. While Goya was firmly into middle age at this point, his face does not depict this. Under the tricorne hat, the artist looks upon the observer with an expression that nears condescension, or perhaps scorn. Goya of this period is confident in his own abilities, as he should be. His rise was borderline meteoric during the late 1770s and through the 1780s.

In the second self-portrait, simply titled Self-Portrait, Goya deliberately takes steps to position himself as an intellectual, a member of the upper class, and an enlightened artist. First, Goya’s high society style of dress connects him to the upper class. It would be very unlikely that a painter would wear such clothes during their work, and Goya is clearly in a staged pose. The tension between his work as a painter and his upper-class dress doesn’t appear to cause any issue for the young artist, as he presents an aura of confidence (perhaps emphasized by the light illuminating Goya from behind, adding further to his self-image as an enlightened artist). In fact, if we look closely, the paint on the palette Goya is holding looks to be the same colors as the painting: Goya appears to be painting himself…painting…the painting. This self-portrait represents a fairly radical departure from his predecessors in the north, notably Rembrandt.

Rembrandt’s 1629 self-portrait, The Artist in his Studio, emphasizes the easel and canvas that takes up the majority of the right side of the painting. The artist, presumably Rembrandt himself, is dressed as one would typically imagine an artist would. The artist’s face is partially hidden in shadow, and it’s difficult to make out much about the artist as he occupies a relatively small part of the painting. On the other hand, Goya himself is the focus of his self-portrait. The artist, not the art, occupies the foreground. Goya’s stance, with legs slightly apart in a clearly triangular structure, seems to whisper about connections to the classical Greco-Roman works. The subjectivity of the Artist, the importance of his Will and creativity, takes the foreground with the Enlightenment in a way that would be unthinkable even to the greats of just a century prior.

Section 2: The End of the Beginning

The Spanish Enlightenment had made serious inroads in Spain by the early 1790s, but the nobility and clergy were hardly going to support modernizing themselves out of existence. However, this natural limit to change would not be the deciding factor in the collapse of the Spanish Enlightenment: each new horror from the French Revolution and its subsequent debacles only caused the Spanish elites to recoil. Now, the revolutionary fervor that had spread from France into its southern neighbor had to be eliminated. The afrancesados (Francophiles) would no longer be tolerated, and the ilustrados/luces (enlightened/“lights”) would have to be extinguished.

This would only intensify as France and Spain declared war on one another in 1793, as part of the War of the First Coalition against the French First Republic. The afrancesados were torn between loyalty to their nation and allegiance to the international project of Enlightenment. The ilustrados who had once received royal support for their reformist ideas shrank from the public eye or switched sides. The Spanish people, the pueblo, largely opposed the reforms of the ilustrados, perceiving their reforms as an unwanted intrusion that would threaten the traditions and culture that had developed over centuries. The pueblo allied themselves with the traditional conservative forces of crown and clergy, and the ilustrados sought to reform the state, economy, and educational system in the name of the very pueblo who rejected them. The conservative union was unstable (and it spawned crises and violence that extended into the late 20th century), but the late 1780s, 1790s, and early 19th century would see a revival of Spanish popular culture, with even the hereditary nobility attempting to imitate the “proletarian aristocrats”, the majas and majos, for their presumably pure Castilian blood and spirit. The bourgeois character of these new aristocrats would eventually be a root for much of the social upheaval as they aristocracy edged closer and closer to the abyss.

Goya himself took this upheaval particularly badly: he suffered a grave illness from 1792-1793. His confidence was shattered, his mental stability was shaken, and his hearing was gone (he would be deaf for the rest of his life). During the next three decades, Goya would witness Spain in the throes of revolution and counterrevolution, war and insurgency, and brutal quests to find some kind of national essence that could give meaning to the suffering that pervaded the peninsula. These titanic struggles would shape Goya, and his artwork would shift considerably. In fact, one can reasonably say that it was this illness and the virulent political environment inaugurated Goya’s second career.

PART TWO: The Late Goya (1792-1823)

Section 3: After the Illness

“In order to distract my mind, mortified by reflection on my misfortunes, and in order to recoup some of the expenses they have occasioned, I executed a series of cabinet pictures in which I have managed to make observations that commissioned works ordinarily do not allow, and in which fantasy and invention have no place” - Goya to his friend, Bernado de Iriarte

Upon recovering from his illness during his self-imposed exile in Cadiz, Goya created a set of eleven small pictures painted on tin. These eleven pictures represent a profound shift in Goya’s vision: dark, dramatic, and sometimes terrifying, they represent a stark contrast to the confident (perhaps even arrogant) younger Goya.

Some have argued that this represents Goya’s plunge deeper into his own internal depths. Malraux stated that for Goya, “it was the discovery…of the peculiar strength of painting, of the power of a broken line or the bringing together of a red and a black over and above the demands of the object represented.” This move beyond a mere representation of the world and into a transfiguration of the world through the artist’s subjectivity is a key element of the philosophy of romanticism (and of modernity) as Charles Taylor has famously discussed in his Sources of the Self.

In particular, Courtyard with Lunatics is a terrifying example of Goya’s dark turn. The courtyard itself appears claustrophobic, boxed in by thick walls, with the only light emanating in from above. The “lunatics” within the courtyard take on a variety of expressions, with a pair fighting in the middle, one looking towards the sky (perhaps for forgiveness) as he appears poised to whip the two combatants, and a pair (one on the left and one on the right) staring at the audience, inspiring foreboding and despair in the viewer. Some have argued that Goya intended this painting as an indictment of the punitive treatment of insanity in highly inhumane asylums. Perhaps inspired by his own illness and self-imposed exile, Goya depicts a vision of the horrible alienation and fear caused by mental illness (and society’s shunning of those who suffered it).

Section 4: The Middle Enlightenment and Los Caprichos

In 1799, Goya released a series of prints that Robert Flynn Jonhson called “the greatest single work of art created in Spain since the writings of Cervantes and the paintings of Velazquez”. This series of prints was called Los Caprichos.

Caprichos 1, another self-portrait, doesn’t appear to be anything special. Goya’s facial expression is somewhat ambiguous, as it could either represent a tired old man, or a self-satisfied enlightened artist looking at the viewer with disdain. The ambiguity only deepens, as the remainder of the Caprichos satirize and lampoon various attitudes, both Enlightened and conservative Spanish.

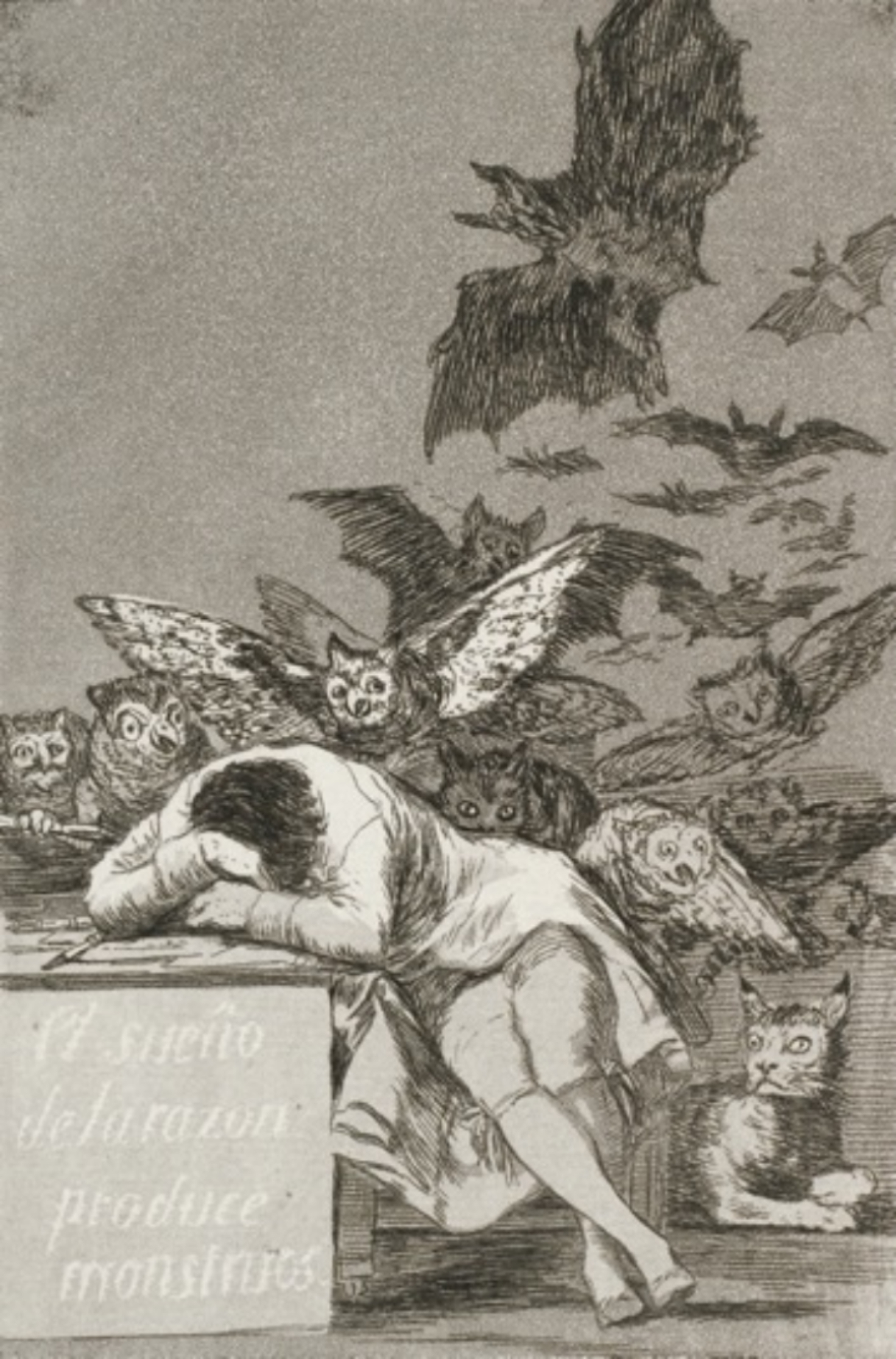

Caprichos 43 is perhaps the most famous of his works: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. On the margin of a sheet containing a study for Caprichos 43, Goya had this to say: “The author’s…intention is to banish harmful beliefs commonly held, and with this work of Caprichos to perpetuate the solid testimony of truth.” On the one hand, the influence of the Enlightenment clearly pervades his writing and work, but the tensions of Enlightenment are present. The sleeping figure may reflect Reason itself, but it may also be a symbol of Goya himself, who suffered the breakdown of his own Reason during his illness. The monsters occupy the painting as the subject, representing Reason, is sleeping. However, Goya is not making an endorsement of Enlightenment, arguing that once reason awakens the monsters will be banished. Instead, it seems more likely Goya is reflecting upon the distressing tensions within his own mind and the janus-faced nature of Enlightenment itself. It is as much a criticism of the ilustrados as it is an endorsement of their ideology. Another interesting note here is the shift to the focus on tapping the well-spring of the artist’s internal imaginative depths. Goya acknowledges the heavy psychic price of the violence and eroticism that can emerge like a flood from one’s own psychic wellsprings (and perhaps hints that this same price may be paid by an “Enlightened” society at large). For Goya, imagination and nightmare, science and ignorance: these are inextricably linked. Reason itself generates Monsters it cannot slay.

Section 5: The Horrors of War

Goya made no prints for a decade after the publication of the Caprichos. The Caprichos would cement Goya’s focus on the people, the Spanish pueblo, which he would continue to focus on for the last two decades of his life. Goya became reclusive following the publication of the Caprichos, but prior to his encounter with the horrors of the War of Spanish Independence. After 1808, Goya became a participant in, and a victim of, the tectonic shifts brought about by revolution and war. Public artist and private man could no longer be separated.

In 1807-08, Napoleon’s French armies invaded the peninsula, and the Spanish people revolted. After the plebeians revolted, France engaged in major reprisals the next day. That day was May 3rd.

Painted by Goya in 1814, his public and righteously indignant response to French imperialism was meant to immortalize the immense courage and suffering of the Spanish people. Goya painted it after the restoration of Ferdinand VII and the expulsion of Spanish liberals. Goya depicted a brave pueblo aligned with Church and Crown against the Godless invaders. The actual Spanish uprisings were notoriously messy (guerrilla bands and juntas of “Right” and “Left” fought invaders and each other), but Goya provided a mythic integrity to the Spanish resistance by exalting the heroism and sacrifice of the people.

But while some of his most famous works exalted Spanish bravery, Goya published 82 prints between 1810-1820 which seem to present a more honest response. The series of prints exhibit such emotional intensity and embrace, such moral & political ambiguity in the depictions of the fighting, that they could not be published in Goya’s lifetime. They only appeared in 1863, 35 years after Goya’s death. The actual name for the series of prints was “The Terrible results of the bloody war in Spain against Bonaparte. And other emphatic caprichos.” Today, they are simply called the Disasters of War.

Goya’s revulsion at the horror and brutality of war, and the savagery of the pueblo alongside the French, is a condemnation of all parties involved, not a celebration of heroic resolve. The Disasters can be split into three general groups: the victims and horrors of war (prints 2-47), victims of famine, death, and burial (prints 48-64), and “caprichos enfaticos” (prints 65-80), which depicted corruption in nightmarish form. While most of the prints were likely finished prior to 1814, the final group was probably conceived after the restoration of Ferdinand VII and before the Liberal coup in 1820, during the nadir of liberal power in the peninsula.

In his final decade of life, Goya’s works were not uniformly bleak, with portraits, religious paintings, and experimental work all being explored; however, the most noteworthy of Goya’s works during this period are the so-called “Black Paintings” he created to decorate the walls of two rooms of his own residence in Madrid. Once a firm believer in the Enlightenment and his own talent, these works painted between 1820 and 1823 cannot be considered celebrations of a revival in truth and reason. These works are primarily grotesque, and include the famous Saturn Devouring His Children and The Witches Sabbath, among others. Nightmarish at best, they seem to allude to the violence and superstition of the Inquisition, but this time with little hope for a better future. The paintings were not meant for a public audience: only Goya, his family, and the few friends willing to visit an old ilustrado saw them. Goya painted them during an epoch when human reason slept; but that does not mean logic had been abandoned. Historian Gwyn Willians wrote “That these monsters are human is, indeed, the point.” Echoing his northern predecessor Bruegel, Goya saw the grotesque and popular as a world opposed to order, rationality, aristocracy, and the ideal. But unlike Bruegel, Goya’s paintings are not picturesque: they are brutal and offer little comfort.

Goya’s life, and the evolution of his artistry, reflects the tensions of the development of Enlightenment. At first self-assured and inspired by confidence in his own artistic subjectivity and vision, Goya’s experiences in the tumultuous aftermath of the French Revolution would shake these foundations of his own belief. Goya was prescient in imagining the union of Enlightenment and barbarism. As Man becomes the measure and source of All, the artists were the first who felt, and sometimes drowned under, the weight of the vast psychic oceans they were forced to plunge into in order to make sense of a world transformed. And perhaps Goya understood before many others that this transformation, so magnificent in its promises, could not overcome the terrors lying deep within human nature.

THIS PIECE IS AVAILABLE IN PRINT FORM IN VOLUME I ISSUE III

ORDER HERE