VERS LE VITESSE D’ÉCHAPPEMENT

Neon Bag

“You are living inside a question.”

“How about ‘Hi Robert, thanks for meeting me instead of just rejecting my unpublishable screed, would you like a coffee?’”

“Would you like a coffee, Bobby?” I was already getting up and walking to the bar.

“No, I’d like a ‘coffee, Robert.’”

“Sure thing.”

I bellied up to the bar and ordered “One Coffee Bobby” loud enough for him to hear.

“One Coffee Bobby coming right up!” Robert shot me a droll look. I couldn’t tell if the barista was messing with me or him. I had brought my own coffee and wasn’t sharing. Their coffee was organic, too, but mine lacked the piquance of a Malayan cat’s asshole and wasn’t ground by an uptalking beardo with a resist-fist tattooed on his neck.

I looked at Robert, forty years old, slouching into an unrecoverable smartphone-neck and a pant size that threatened to outpace his age. He had a boat he called a ship and didn’t own, a Maryland townhome the bank owned and he couldn’t legally defend, two good kids from a wife who owned him utterly and that was about it. Our college days were more promising, believe me, but he got busy with his now-wife and he withered, shriveled right up. His conservative vanity mag--the better circulated of his two basically vestigial organs--was small but mildly influential. It was funded more by benefactors than subscribers despite the constant and unctuous fundraisers.

I had offered Beardo a half nod while he looked askance at the empty tip cup. He didn’t answer. I thought how fun it would be to screw with him, and how much it would cost me, and then about how massive he was, and that biting my lip was free. Oh, you want the working man to beg? I grind beans, man, not an organ, you elitist f... he was coming over the counter, he was 6’5” tall, he was going ballistic, and I was reconsidering. I had taken “Mister .45” out for a little exercise and still had him on my hip. There was no good ending to that story. Just then he was watching me slide his exact change to the farthest end of the counter and walk away.

Robert hadn’t caught the particulars of our silent battle but I gathered from his wearing his own shoulders like earmuffs that he knew it was unfriendly. I think he was expecting violence and wasn’t planning on helping: I had fought Bobby’s battles in elementary school, in high school and college, and he’d spent the rest of his life avoiding conflict altogether. Which explains how he got the second kid and the bully wife, and had finally buried himself in boat debt during a paroxysm of pretty understandable selfishness. He had never fought to know whether he could fight, or what life would be like knowing he had survived--or even won--a fight.

“You’re living inside a question,” I reprised as I sat down, “and so you can’t imagine living in the solved problem. Your life has been a dispiriting bargain for mere existence, the only violence you’ve ever known has been daily beatings by the government, by bill collectors, by the HOA, by your slop-poisoned endocrine system, and maybe this conversation.”

By the end of that rant, having summed up the pathetic state of my friend, I thought about skinning my .45 and pointing it at him right there at the table. I was pressing a half-inch steel ring of holy matrimony into his third eye and demanding he publish my piece, demanding he stood up for something, demanding he lived God damn it. I wanted to scare some blood into his withered old prick. I wanted him to ventilate that mutant barista. I wanted to ventilate that mutant barista. But I wanted published more and everybody else had said no.

“Your piece was about Ian Smith, it was about a once-country about which nobody knows a thing, it was full of quotes nobody can reference--which you likewise didn’t reference--” Bobby was huffing about the piece but I think what had steamed him was finally processing my rant: I’d called him a neuter, and just then he was a babbling neuter. “...so okay, you don’t like how I live, I’m a big disappointment, you don’t like my magazine--but you want me to publish you in that magazine? I’m living inside a question? Are you on drugs?”

Beardo was hovering over Robert’s cup and saucer at the counter. His Coffee Robert was ready and it was time for a little class war over how it was gonna get to the table. I allowed for a dramatic pause, indicating that I hadn’t been listening exactly, and then assiduously avoided eye contact with the angry coffee giant who had marched over and tried his best not to slam Robert’s coffee on the table.

“A long time ago in an Africa far far away,”

“You’re lucky this coffee is so good. Will you get to the point?” he mumbled into his cup.

“The point is there’s very few men of substance on earth.”

“That’s not new. Ow! Damn hot.”

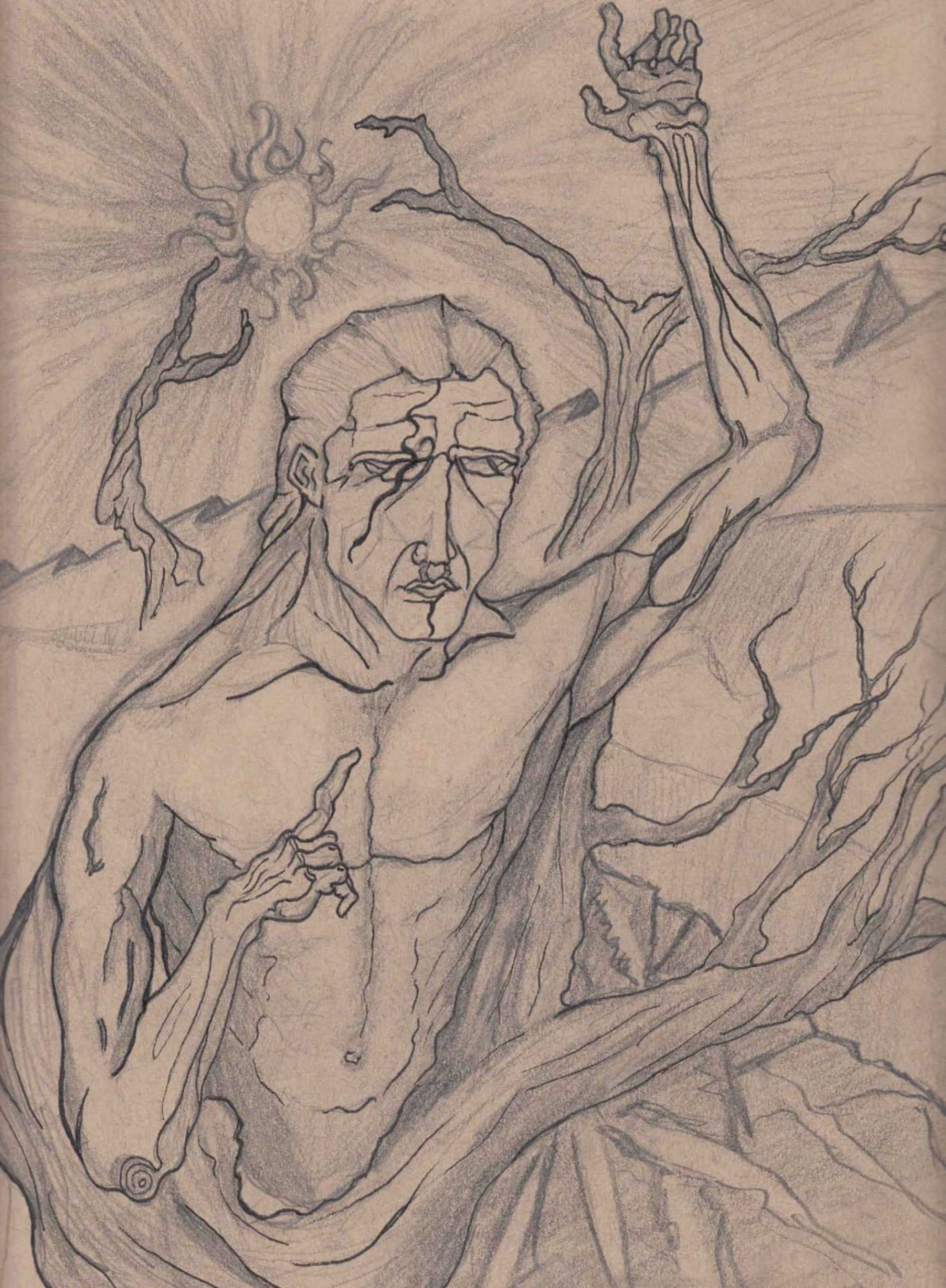

“That’s my point: that their lack isn’t new. The lack of real grit, of deranged hormone levels, of fanatical self-belief, an engorged spirit of vitality, there are very few such men!” Such Men. The kind whose births are rare micro-speciation events triggered by sugar-fiend mommies and the whispers of the Gods. I was intoning halfway to a doomsday preacher, “ask Clearchus, ask Caesar, ask Christ, or Washington, or Stalin.”

“Or ask Smith?”

“Ask Smith. Exactly.”

I allowed a few moments for the associations to weave themselves together in his mind. Bobby knew plenty about the subject in my piece. We had read all about Rhodesia on internet forums, acquired out of print books about it. We had both been deeply fascinated by the bravery of these young men fighting a battle we now knew had been hopeless from the start. It was romantic but I wasn’t satisfied with romance; longing for something I couldn’t experience made me feel sick. Nostalgia is a black abyss of shed skins and broken mirrors dimly gleamed by vague impressions you can’t be sure are your own. Nostalgia was inside The Question. I wanted out.

Robert finally looked at me, “Smith was living inside The Question?” He was. “He was, yeah.” I was baiting him, and he took it, demanding to know how I could call a man who had forged an independent European state inside Africa a spiritual homebody. I answered that his vision was limited by his belief system. “Properly understood, Smith wasn’t forging a bold new future. Smith wasn’t tearing through a paper horizon into a dark frontier. Hell, he had stretched Westminsterism beyond breaking--into grotesquery--to avoid breaching that frontier. To avoid truly winning.”

Robert’s mouth hung open, with his lower lip tortured out of symmetry by his thoughts, “Are you shitting on Ian Smith now? Who’s supposed to like this piece?”

“The point is Trump as Smith, Bolsonaro as Smith, whoever next as Smith unless we wield Smith now, as he really was, and strike whoever comes next while he’s hot, before he becomes the next scrap of iron on the slag pile of history. Before we’re saddled with another generation of young men neutralized by wistful romance.”

It wasn’t good enough to promote a ‘brave failure’ or ‘to have almost’ yet again. Rhodesia’s independent identity had been a fractal, it was a derivative of its origins. It wasn’t new. Smith was at the frontier but wasn’t of the frontier. He was highly respectable, he was decent, he was firm, he was genteel, he had a great vegetable garden, and he was a great man! But he was not Such Men as could forge a new reality. “Smith could hardly forge a hard new identity for himself,” I continued, “let alone a country, and he remained respectable when a scoundrel was needed, reactive when aggression was needed, and loyal to the disloyal when total paranoia was needed.”

Robert sat across the table, now frozen, now lost in thought, now staring past me. I think he wanted to stomp on my foot, or throw coffee at me--I have that effect on people--but as thoughts flickered past the back of his eyes and he began to heat up a look would come over him. I think he was remembering when I threw his cheating girlfriend out of our apartment for him--he married her anyway,

“Imagine all those brave young men living in the bush,”

or when I brained that pushy manlet at the Virginia Beach bar he’d run from the previous night,

“fighting a guerilla war against a faceless enemy in his own native territory,”

or when his older brother beat up his school bully for him...

“their faces fading out of family photos,”

...one, or some, or all of those had led to him biting a quivering lip.

“or whatever sappy dramatization stirs up your blood, Robert, if you have any left.”

The silence that followed was that of a man who knew in his heart what must be done and that it would destroy his “life” to do so.

“We need men who gamble and lie. Men who tell seven lies within a hundred yards. Do you understand?” I left it hanging in the air. There was a slight tremor in his right hand as he brought the mug to his lips. He exhaled his reply with the heat of the sip, “Yeah.” I heard the heels of his shoes bump up against the legs of his chair. The conversation had chafed him badly. He was gonna run. I mean really run. Away. Just like in college. Run home to the bills and the mortgage and the boat. Just then I was thinking the world had no use for one more runner.

Beardo had disappeared into the back room and as I leaned in to grab Bobby’s hand my right arm, still under the table, jumped up and gave a jolt. We stared dazed and deaf at each other, ears ringing, for an instant before Robert’s nerves caught up and he let out a wailing klaxon scream. I grabbed his hand and held him in place at the table, staring intently, until his hand suddenly yanked back and the wail was replaced with a moment of stunned silence and incredulity, “What the hell’s the matter with you?” he shot back, rubbing a half-crushed hand. “Are you sure that’s coffee you’re drinking?” I heard that one through the tabletop. I was already bent down checking with my own incredulity on his perfectly not-shot foot.

“Trump had the big office and he lost it without a fight; Bolsonaro same thing. The popular disturbances of a disgruntled minority in both cases led only to their humiliation, punishment, and dissolution. The military were beating Bolsonaro’s supporters in the streets while he was getting a sandwich at a Ft. Lauderdale Publix. Is that leadership? The other’s supporters are languishing in prison, their lives ruined, abandoned and crushed by enemy lawfare. Is that leadership?”

Robert looked at me like he suddenly had all the answers, and he pounced, “They followed leaders who had no real chance of changing anything. Certainly not the entire system. Not the levers of power, not the bureaucracy, it was the dead cat bounce of an exhausted demographic. The ones too young to realize it was all just a grand FU to the system got...” he trailed off; I picked up, “what they deserved?” “No, but what was coming to them.” he quibbled. They hadn’t deserved it. They deserved leadership and it was clear to me now that the next young men would have to make their own.

“Robert, don’t you think there is a sort of nobility of the spirit in seeing the windmill for what it is and tilting anyway, in maybe losing everything, even to turn the clock back to the halcyon days of 6 years ago? In taking at least one step toward the Solved Problem?” Smith had seemed to do better than similar figures in our age but the age had been different; and he still ended up out of power with his supporters in flight or in trouble. They lost their country, their farms, their lives. Was that leadership? I wasn’t sure if I wanted to convince Robert anymore. Or anyone. He was mute now but he wasn’t running so I continued, “You know in the end there was an operation planned, men were in place, by a bridge, with certain special pyrotechnics, the enemy was going to drive over this bridge, but Smith couldn’t do it. He couldn’t have lived with himself. He refused to give the order.”

In truth when Smith at last saw the horizon of a new frontier, and the destruction of his enemies, he refused to fight. Until that point the fight had been parliamentarianism by other methods. It was negotiation against change--negotiation to maintain much of what had brought him there. The handful of traitors who subverted him and the anti-imperialists in the Foreign Office were scum but good men were just as much to blame. In the end he couldn’t betray himself. His loyal friends, though they were otherwise Such Men, couldn’t betray him either. They had been worth seven lies in a lifetime and Smith needed a tighter schedule. The whole country did. Smith’s last chance for victory drove safely over that bridge.

“Well this isn’t that era, and it isn’t 6 years ago, and I don’t print the Volkischer Beobachter! I can’t publish an attack on two of the most beloved conservatives of the past 60 years.” Robert looked embarrassed for the crude comparison. He wished he had the Beobachter’s circulation. “Our subscribers would cancel, our benefactors might even drop us, and then,” Robert sounded final as I exhaled pointedly and dipped my head under the table: foot still not-shot. Opportunities for radical action remained.

“Yeah, enjoy that boat...” I mumbled, drawing my pistol quietly, Robert cut back in like a hurt woman, “I will! And my house, and my wife, and fuck you very much! Judgmental asshole, you think just,” and the rest happened so fast I could hardly make sense of it: A pair of black boots, Robert’s feet lifting right off the floor, I banged my head up against the table so hard it turned the damned thing over. Standing up I saw a bearded blurry giant with a milk steamer under his arm and the power cord wrapped tightly around Robert’s neck, 80 years of agitprop and rabble rousing focused through 3 feet of black pvc and copper wire.

My head was swimming. The bearded giant was spitting through his teeth a litany of everything “people like us” had done wrong to everybody else. Robert’s trachea was being crushed on their behalf. His few fingers between the cord and his neck were mangled, fat and purple. Here we were again. I dropped the magazine out of my piece and turned it around with the grip toward Robert, marrying it and its one chambered round firmly to his flailing hand. I looked past the bulging veins in his face and into his bloodshot eyes and walked away. We didn’t need that kind of Robert anymore.

I pulled the door open and the coffee shop flooded with the cacophony of traffic and construction. Nobody outside had noticed the struggle. Seconds passed that felt like hours. I made myself clear over the city’s jungle din as I let go of the door and stepped out, “You are living inside a question.”

THIS PIECE IS AVAILABLE IN PRINT FORM IN VOLUME II ISSUE VI

ORDER HERE